Getting CO₂ Specifications Right: The Critical Difference Between ppm by Mole and ppm by Volume

28 January 2026

Citation: IEAGHG, “Getting CO₂ Specifications Right: The Critical Difference Between ppm by Mole and ppm by Volume”, 2026-IP02, January 2026, doi.org/10.62849/2026-IP02.

Introduction

Measurement and reporting of CO₂ concentrations underpin many activities in subsurface engineering, reservoir modelling and CCS operations, including metering, monitoring, and regulatory compliance. In these settings, concentrations are often expressed in parts per million, but the basis of ppm is not always stated clearly. As a result, ppm mol and ppm vol are frequently treated as if they were interchangeable, and distinctions between mole based, volume based and mass-based definitions are overlooked.

In practice, the choice between ppm mol and ppm vol has a direct impact on calculated concentrations, especially when gas composition, temperature and pressure deviate from simplified assumptions. Reservoir conditions, pipeline transport systems and process units can span wide operating ranges and involve complex gas mixtures that contain impurities and water vapour. Under such conditions, a simple one-to-one substitution between ppm mol and ppm vol is not valid, and inappropriate conversions can introduce discrepancies that reach up to a factor of three (for example composition of CO2, methanol and water) in reported values.

These issues have practical consequences across the CCS chain. Misinterpretation of concentration units can affect reservoir model inputs, the assessment of containment performance, the design and interpretation of monitoring programmes and the reconciliation of laboratory measurements with field data. In metering and monitoring applications, where decisions on alarms, remediation actions and compliance are often based on concentration thresholds, errors in unit handling can propagate into significant technical and regulatory outcomes.

The discussion by Abdul’Aziz Aliyu (hereafter AA, IEAGHG), Joop van der Steen (hereafter JvdS, Shell) and Dr Panteha Bolourinejad (hereafter PB, Shell)presented in this paper is motivated by repeated observations of such inconsistencies in project reports, regulatory submissions and scientific communication. By clarifying the distinction between mole-based and volume-based ppm, setting out the theoretical basis for conversion under realistic operating conditions and illustrating the implications through case studies, the paper seeks to provide a common reference for engineers and scientists. This context frames the need for clear unit definitions and consistent conversion practice in order to improve the reliability of CCS operations and environmental reporting.

Discussion

AA, IEAGHG: As CCS scales globally, more projects and jurisdictions will rely on shared specifications and reporting formats. CO₂ in CCS systems is often handled in the dense phase, near the critical region, where small changes in temperature or pressure can affect its behaviour.

So, here is the first question: why does it matter, and how big an impact can a seemingly trivial mix-up between ppm by mole and ppm by volume actually have on our phase behaviour predictions, flow calculations and overall CCS system reliability?

JvdS, Shell: This matters because CO₂ behaves very differently near its critical point (31.1°C and 7.38 MPa), conditions that CCS systems often operate under. A mix-up between ppm by mole and ppm by volume can lead to serious errors, such as incorrect phase transition predictions, miscalculated flow rates and injection volumes, faulty sensor calibration and data interpretation, and inaccurate metering, monitoring, and reporting. These mistakes don’t just stay on paper; they can cascade into reservoir models, operational decisions, and even regulatory compliance, creating inefficiencies and safety risks. The challenge grows when streams contain multiple components like N₂, O₂, CH₄, water, methanol, or glycols. Their varying molecular weights mean that assuming ppm mol equals ppm vol can distort the actual composition and behaviour of the mixture. In short, what seems like a minor unit error can undermine the reliability of an entire CCS system.

AA, IEAGHG: This conversion becomes particularly important when dealing with gas-dominated streams (or systems) that contain components which are in the liquid state in their pure form at standard conditions (1 bar and 15°C), and when operating under conditions that deviate from ideal gas behaviour. Once the compressibility factor Z drifts away from 1, how safe is it to continue assuming that ppm mole and ppm volume give us an identical view of what is actually in the line? Where does it really matter?

PB, Shell: When a system deviates from ideal gas behaviour, assuming ppm by mole equals ppm by volume becomes risky.

Components like water, methanol, ethanol, and glycols are liquids at standard conditions (1 bar, 15°C). These components appear in trace amounts in CCS streams. These polar components interact strongly with CO₂ and other impurities, influencing their behaviour as well as their sampling and measurement. The difference between ppm mole and ppm volume is pressure and temperature dependent and can be substantial.

In short, under non-ideal conditions, equating ppm mole with ppm volume can distort composition, affect flow predictions, and compromise measurement reliability. Proper conversion is essential for accurate specifications and safe operations.

AA, IEAGHG: If ppm mole and ppm volume can be treated as equal for lighter gases like methane and ethane under typical CCS conditions, how clear are we in practice about when that shortcut is valid and when careful unit conversion is essential for CO₂ specification compliance, sensor calibration and data interpretation?

PB, Shell: For lighter gases such as methane, ethane, and other typical gaseous contaminants, the ideal gas approximation is often sufficient. Under typical CCS operating conditions, these gases exhibit behaviour close to ideal, and ppm mole can be reasonably assumed to equal ppm volume.

AA, IEAGHG: In many CCS workflows, CO₂ specifications and models are expressed in ppm mole, while field instruments and environmental monitors tend to report in ppm volume by default. How does this mismatch between ppm mole in models and ppm volume in measurements show up in real projects, and what can go wrong if we do not handle that conversion explicitly? In practice, how do we convert between ppm mole and ppm volume when we are working with real project streams?

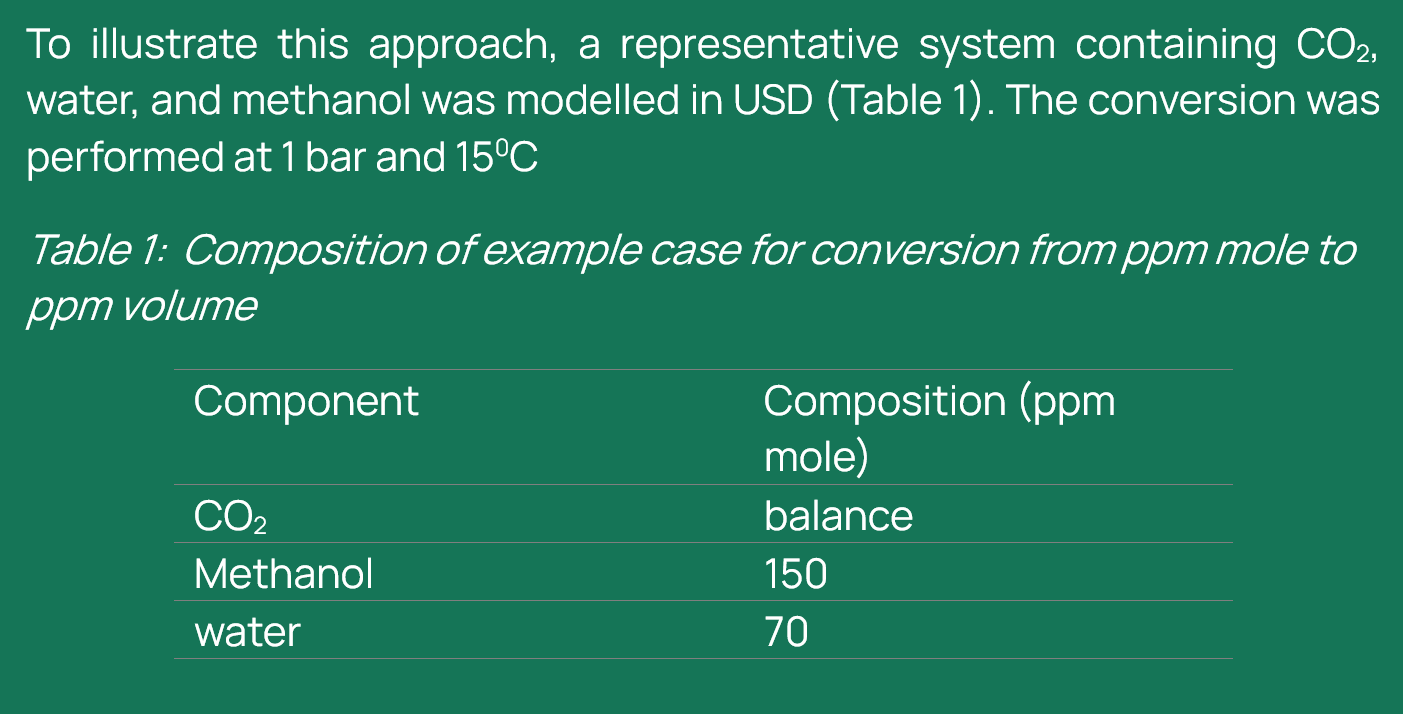

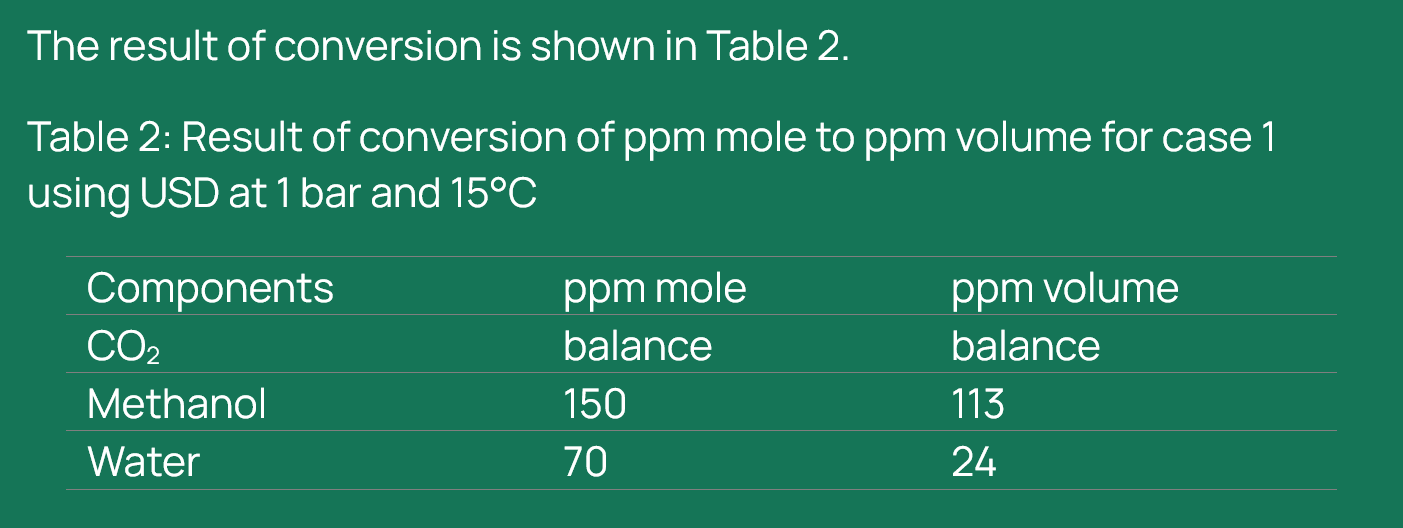

PB, Shell: To address this, we integrated conversion steps into standard CCS workflows using both commercial and Shell proprietary tools. For thermodynamic modelling and gas stream analysis, platforms like Aspen HYSYS, UniSim Design (USD), and Shell’s STFlash are commonly used. In our study, we relied on USD (automated) and STFlash (manual) to calculate accurate properties under real operating conditions.

Using USD, a direct conversion is possible (only at standard conditions), where the software can automatically translate mole fractions into volume fractions. However, when working under non-standard conditions such as elevated pressures and temperatures typical in CCS operations or when access to commercial simulation tools is limited, a manual calculation approach becomes necessary.

This manual method involves using the mole fraction of each component in the stream, calculating its molar volume under the given conditions, and then determining the individual volume contribution of each component. From there, the volume fraction (ppm vol) can be derived. For this study, we used Shell’s internal STFlash tool to obtain accurate thermodynamic properties of the mixture for a representative CO₂-rich stream.

USD (automated): This commercial process simulation software allows users to input gas compositions in ppm mole, and when operating under standard conditions (typically 1 bar and 15°C), it can directly compute the corresponding ppm volume values as part of its built-in thermodynamic package. This feature simplifies the conversion process and ensures consistency in unit handling within simulation environments.

For the direct conversion of ppm mole to ppm volume, the workflow in UniSim Design (USD) begins with the selection of an appropriate equation of state (EOS). In this study, the CPA EOS from the Shell proprietary physical properties (SPPTS) package was used due to its suitability for modelling systems containing polar components such as water and methanol. Once the EOS is defined, a new stream is created, and the concentrations of the components of interest, CO₂, methanol, and water are entered in ppm mole. Following this, the conversion conditions must be specified. For this case, the pressure was set to 1 bar and the temperature to 15°C, representing standard conditions for comparison (it should be noted that even if different pressure and temperature conditions are selected, in this package, the conversion will be done at standard conditions). Following that, selecting “Basis” bottom in the composition mole fraction table ‘‘Liquid volume fractions’’ can be selected and the numbers automatically change to volume fractions.

It is important to note that UniSim Design performs ppm mole to ppm volume conversion strictly under standard conditions, regardless of any changes made to pressure or temperature settings in the stream. Even if the user specifies different operating conditions, the software defaults to standard reference conditions (1 bar and 15°C) for the conversion. This behaviour must be carefully considered when interpreting results, especially in CCS applications where operating conditions often deviate significantly from standard. Failure to account for this default behaviour may lead to misrepresentation of concentration values and incorrect assumptions in downstream calculations.

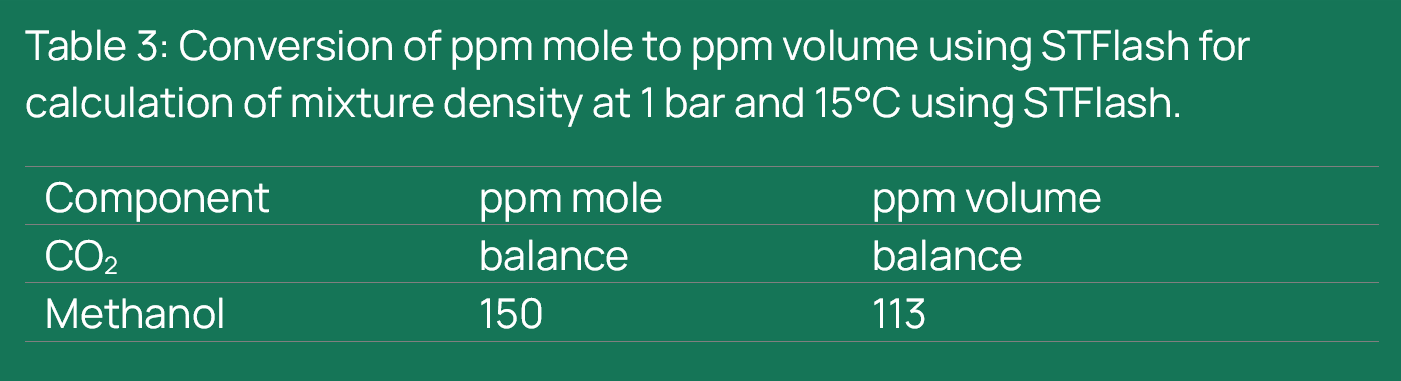

PVT/thermodynamic packages (manual): In cases where commercial simulation tools (like USD) are unavailable or when conversion under non-standard conditions is required, the ppm mole to ppm volume conversion can be performed manually using thermodynamic data. This approach relies on calculating the molar volume of each component in the mixture and applying mole fraction-based scaling to determine individual volume contributions. For this study, we used STFlash, Shell’s internal thermodynamic package, to obtain accurate property data. The conversion was carried out at 1 bar and 15°C, following these steps:

Input the gas mixture composition into STFlash and perform an isothermal flash at the desired pressure and temperature

Run dew point pressure calculations for each of the pure components in the mixture to obtain their molar volumes in the liquid phase under the same conditions.

Using the mole fraction and molar volume of each component, calculate the individual volume contribution. From these, derive the volume fraction (ppm volume) for each component.

This method provides flexibility for analysing systems under varying operational conditions and ensures accurate conversion.

AA, IEAGHG: So, you did conduct some sensitivities. What does the analysis tell us about how operating pressure and temperature affect the conversion between ppm mole and ppm volume? Building on that, could you share a concrete example from a CCS project where confusion between ppm mole and ppm volume actually changed, or would have changed, an operational or design decision?

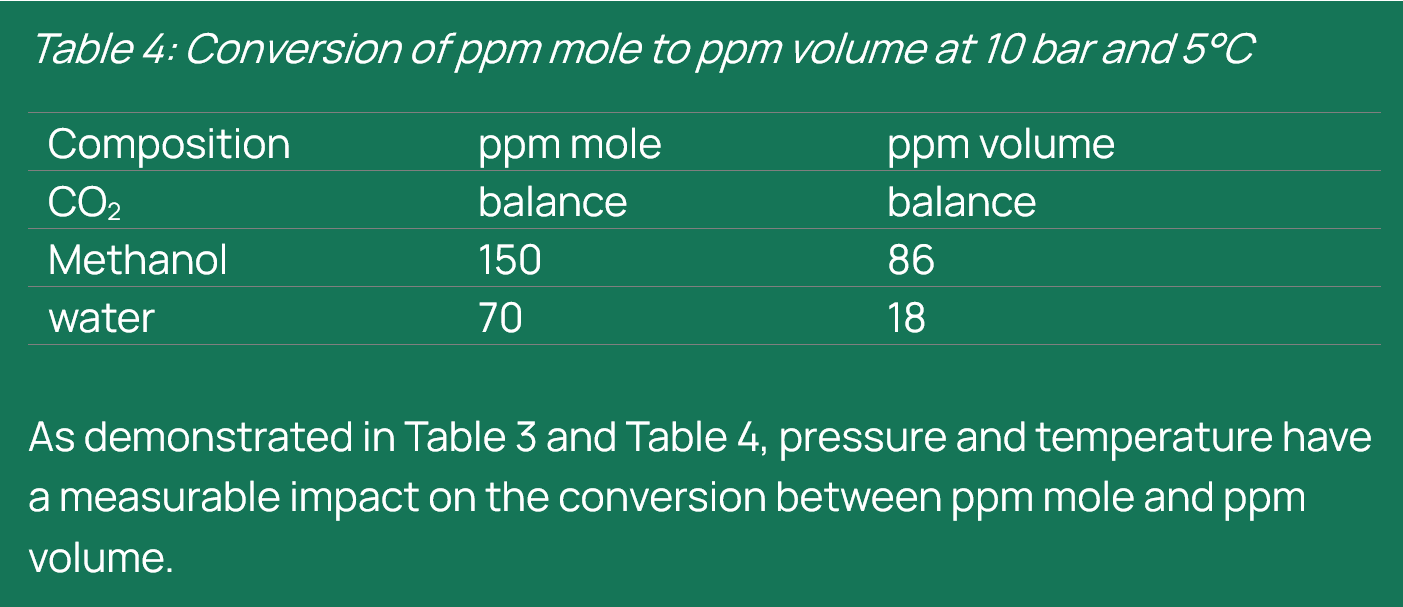

PB, Shell: Using the same CO2 composition defined earlier (CO₂, methanol, and water), the conversion was carried out at 10 bar and 25°C. This allowed us to assess how deviations from standard conditions influence molar volumes, phase behaviour, and ultimately the resulting volume fractions. The calculations were performed using STFlash, with updated thermodynamic properties obtained through isothermal flash and dew point pressure simulations. This comparison demonstrates that relying solely on standard-condition assumptions can lead to significant discrepancies in concentration reporting and interpretation if different pressure and temperature conditions are required.

As demonstrated in Table 3 and Table 4, pressure and temperature have a measurable impact on the conversion between ppm mole and ppm volume.

AA, IEAGHG: Based on what we now know, what should change in the way CO₂ specifications, contracts and permits are written in practice, for example, around stating the ppm basis and the reference pressure and temperature?

PB, Shell: CO₂ specifications, contracts, and permits should explicitly state the ppm basis, whether it is by mole or by volume and, in case of ppm volume, the reference pressure and temperature. This clarity avoids ambiguity in compliance checks and operational decisions.

AA, IEAGHG: For colleagues who are not thermodynamics specialists but routinely deal with ppm values in specifications, models and monitoring reports, what simple rules of thumb or good practice would you suggest so they can avoid ppm-related mistakes?

JvdS, Shell: A few simple rules can help avoid ppm-related mistakes: Keep units consistent across specifications, models, and reports. Agree upfront on the basis, preferably the pressure and temperature independent ppm mole (or the less practical ppm mass). Document any deviations clearly and communicate them to all stakeholders. When in doubt, convert explicitly rather than assume equivalence, especially for non-ideal conditions or multi-component streams. These steps prevent confusion and ensure reliable data interpretation throughout the CCS value chain.

AA, IEAGHG: Right! Any final thoughts or closing remarks

PB, Shell: The distinction between ppm by mole and ppm by volume becomes critical in practical applications such as impurity tracking, metering, monitoring, and regulatory reporting. Consistency and accuracy are essential. Knowing the difference, performing proper conversions when needed, and being mindful of pressure and temperature conditions are key to avoiding costly mistakes.

JvdS, Shell: In CCS workflows, CO₂ specifications are often expressed in ppm by mole, especially in simulation environments and thermodynamic models. However, many field instruments and environmental monitors report concentrations in ppm by volume. If this conversion is overlooked, misinterpretation can occur, particularly for polar components like water and methanol, which behave very differently from ideal gases. Proper handling of these differences is essential for reliable operations and compliance.

Conclusion

The foregoing exchange underscores an important potential source of error, namely the distinction between parts per million by mole (ppm mol) and parts per million by volume (ppm volume). This difference can no longer be dismissed as a minor technicality. A seemingly minor ppm basis mismatch can materially change the interpreted composition and, in turn, distort phase behaviour predictions, flow calculations, and the assumptions embedded in reservoir models and transport system design.

If this mismatch is not handled explicitly, errors can propagate into metering and monitoring, sensor calibration, compliance checks, and operational decision-making. To avoid ambiguity and prevent errors propagating into operational decisions and reporting, specifications should explicitly state the ppm basis and, where relevant, the reference pressure and temperature. Workflows should adopt a clear rule-set, including maintaining unit consistency end-to-end.

Other articles you might be interested in

Get the latest CCS news and insights

Get essential news and updates from the CCS sector and the IEAGHG by email.

Can't find what you are looking for?

Whatever you would like to know, our dedicated team of experts is here to help you. Just drop us an email and we will get back to you as soon as we can.

Contact Us Now