UKCCSRC Direct Air Carbon Capture and Storage (DACCS) Workshop

18 December 2025

UKCCSRC organised a workshop at the University of Sheffield, titled “Deploying Direct Air Capture in the UK: Exploring integration and synergies with UK CCS deployment”. IEAGHG’s Tim Dixon attended and presented in person, and Jasmin Kemper presented remotely.

On 8th December, UKCCSRC organised a workshop at the University of Sheffield, titled “Deploying Direct Air Capture in the UK: Exploring integration and synergies with UK CCS deployment”. IEAGHG’s Tim Dixon attended and presented in person, and Jasmin Kemper presented remotely.

Tim Dixon (IEAGHG) gave the opening talk on global carbon market developments for engineered carbon dioxide removal (eCDR). As this is a relatively recent and developing topic, Tim started with the basic principles for carbon markets and removals, then brought the attendees up to date with the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism’s two standards on Removals (2024) and Reversals from removals (2025). He also mentioned eCDR in other carbon markets, including aviation, and the new IPCC work coming on a methodology for CDR in national inventories.

Felix Clarke (DESNZ) provided key takeaways from the ‘Whitehead Independent Greenhouse Gas Removal (GGR) Review’[1], which was commissioned by the UK Government and published in October 2025 and makes the following five headline recommendations to the UK Government:

- The Government should develop a GGR Strategy to outline the contribution of GGR solutions required to meet carbon budgets and net zero.

- The Government should establish an Office for Greenhouse Gas Removals to produce more coordinated action on GGRs, and to enable quicker and more efficient rollout of policy and project deployment.

- The Government should adopt a strategic aim to minimise the use of imported biomass feedstocks.

- Amend and rename the sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) Mandate to become a Net Zero Aviation Mandate, with a trajectory that means that by 2045 all flights taking off from the UK are made climate-neutral. The amended Mandate should drive procurement of both SAF and permanent GGRs, with competition between these solutions.

- The Government should exploit UK growth opportunities by positioning the UK as a leader on GGRs and in international climate cooperation, making use of the UK’s comparative advantages in science and technology, CO2 storage potential and financial services.

With regards to DACCS in particular, he noted that in the Climate Change Committee’s 7th Carbon Budget, DACCS had a lower cost than SAF per tCO2, and some more specific recommendations include that the Government should assess the feasibility and opportunities for energy and co-product synergies for low-temperature DACCS plants based on waste heat such as from nuclear, data centres and other sources; and to develop a full standard.

Cameron Henderson (DESNZ) gave an overview of the ‘UK GGR Business Models’[2]. The GGR Business Model aims to incentivise private investment in large-scale GGR by providing revenue support for 15 years, under a contract for difference (CfD) mechanism. The Reference Price will reflect the price of GGR credits sold into the voluntary carbon market (VCM), so the priority here is to use the VCM demand to support GGR deployment at the lowest cost to the Government. The HyNet Track-1 expansion Project Negotiation List (PNL) includes two GGR projects, which will now proceed to the negotiation phase. The UK has published a Government Response on integrating GGRs into the UK Emissions Trading System (UK ETS) and six principles for integrity in VCMs. Further, the UK has commissioned the British Standards Institute (BSI) to develop a GGR standard (the BSI has published fast-track FLEX standards on DACCS[3] and BECCS[4] in July 2025).

Jasmin Kemper (IEAGHG) presented on the recently published IEAGHG report ‘The Value of DACCS’[5],[6]. This study critically assessed the role of DACCS in the wider energy transition (down to the regional level), accounting for key factors, including carbon removal efficiency, timeliness, durability, land footprint and techno-economic performance. DACCS cannot be treated as a standalone climate solution. Instead, its environmental effectiveness, scalability, and cost competitiveness are inextricably linked to the surrounding energy system, infrastructure readiness, and global policy context. Key insights include:

- Efficiency is largely constrained by energy carbon intensity (CI) — DACCS must be coupled with deeply decarbonised power to achieve net-negative outcomes.

- Timeliness hinges on early action: rapid scale-up and co-development with clean energy are required to meet mid-century targets.

- Durability is only guaranteed through geological storage; while utilisation may offer short-term removals, it cannot substitute permanent sinks.

- Land footprint of DACCS is lower than many nature-based solutions, but still sensitive to energy source and siting logistics.

- Cost is currently dominated by capital expenditure, but can fall substantially with standardisation and learning-by-doing.

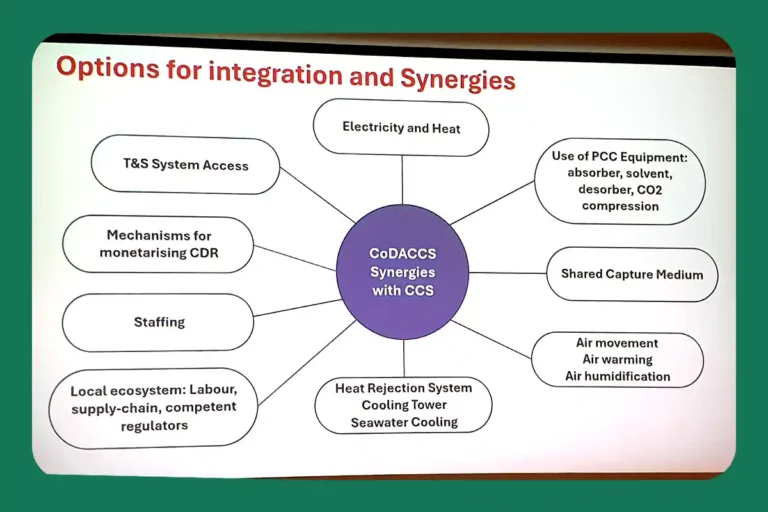

Mathieu Lucquiaud (University of Sheffield) presented on ‘CoDACCS: Combining DACCS with point source capture’. Options for consideration when integrating CoDACCS with point source CCS include:

- Electricity and heat

- Use of post-combustion capture (PCC) equipment

- Shared capture medium

- Air movement, warming and humidification

- Heat rejection system, cooling tower and seawater cooling

- Local ecosystem: labour, supply chain, regulators

- Staffing

- Mechanisms for monetising CDR

- Transport and storage (T&S) system access

Jesse Thompson (University of Kentucky) talked about ‘Biological contamination in DAC’ systems. Biological contamination here includes, e.g., insects, particles, fibres, fungi and other air contaminants. 500h of testing was undertaken with a small-scale DAC apparatus between May and August. Slime growth in the tubing system was detected, and 80% of water samples showed bacterial or fungal growth. Surprisingly, considering the pH, the KOH solvent also showed fungal growth after 200h of testing. The conclusions are that macro- and micro-contamination can happen in DAC systems and thus multiple stages of filtration might be required for mitigation. However, when using filters, there will be a trade-off in terms of pressure drop/costs.

Matthew Joss (Energy Systems Catapult) presented on ‘The siting of DACCS in the UK’. In this work, three different scenarios of supplying waste heat for DACCS in the UK were assessed. In the first scenario, enough waste heat (WH) from nuclear and other thermal power plants is available to supply both DACCS and homes, and CCS roll-out is not delayed. H2 will be used to power DACCS as well, mostly produced from biomass. In case of high DACCS deployment, biomass will be diverted to power, and WH, production. In the second scenario, no nuclear WH is available, thus DACCS is supplied by other thermal power plants and biomass H2, and CCS roll-out is not delayed. As with the previous case, if DACCS deployment is high, biomass will be diverted to power. Though in this scenario, homes will have to be supplied by an alternative source, such as heat pumps. In the third scenario, nuclear WH is available, but CCS roll-out is delayed. Nuclear and other thermal power plants will supply both DACCS and homes with WH. Delays in CCS will reduce the H2 volume and use in industry and transport will be prioritised. If DACCS deployment is high, additional electricity from power plants needs to be supplied to DACCS. Overall, 19.5 MtCO2/yr of WH-powered DACCS requires approximately 26 TWh/yr of WH. Nuclear power plants are the preferred option, as they produce the most WH and thus reduce infrastructure requirements. A 3.6 GW plant has enough WH to power ca. 9 MtCO2/yr of DACCS. Initial estimates indicate that industrial WH in the UK could power ca. 6 MtCO2/yr of DACCS. Co-location of nuclear and DACCS would have the added benefit of electricity supply to the DACCS plant.

Sam Karslake (Committee on Climate Change (CCC)) gave an overview of ‘DACCS deployment in the UK’. In the Balanced Pathway, 60% of emissions reductions are from electrifying key technologies and decarbonising and expanding electricity supply. Smaller but also important contributions come from low-carbon fuels and CCS, as well as nature-based solutions (NBS) and eCDR. The biggest contributions within the eCDR category are made by BECCS pathways, and the rest by DACCS and enhanced rock weathering (ERW) and biochar (BC). For net zero in 2050, NBS solutions are used to offset residual emissions from the agricultural sector and permanent eCDR is used to balance residual emissions from outside the agricultural sector (e.g. industry, aviation, waste). All removal costs are highly uncertain at the moment, with DACCS costs depending on assumed global deployment and learning rates and BECCS costs not including the value of the energy or fuel produced. Current CCC estimates are around £240-340/tCO2e for DACCS, £220-400/tCO2e for BECCS, and £80-200/tCO2e for ERW/BC. In the Balanced Pathway, DACCS deployment is especially linked to aviation, as this sector is a key driver for hard-to-abate residual emissions. Thus, about half of the CO2 captured by DACCS is sent to permanent geological storage, and the rest is used for synthetic shipping and aviation fuels.

Ben Wetenhall (Newcastle University) talked about ‘Key characteristics for CO2 transport and storage systems: remote transport, CO2 flow balancing, CO2 purity’. There are three main areas of key challenges when DACCS is involved: 1) infrastructure and integration (i.e. integrated planning of capture, transport and storage to ensure efficiency and reliability), 2) logistics and operations (i.e. flow balancing and dynamic scheduling in case of remote locations and/or T&S capacity constraints), and 3) open strategic questions (i.e. decisions on co-location, storage prioritisation and alternative transport modes).

The workshop ended with a discussion on how UK DACCS could compete globally. It was observed that the UK has a good economic and regulatory environment for DACCS, although capital costs are high.

Overall, it was a fascinating workshop. Thank you, Mathieu Lucquiaud and colleagues, at UKCCSRC.

[1] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/68f8d27a0794bb80118bb764/independent-review-of-ggr.pdf

[2] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/68ad77c2969253904d1557ff/greenhouse-gas-removal-business-model-summary-august-2025.pdf

[3] https://knowledge.bsigroup.com/products/direct-air-carbon-capture-and-storage-daccs-quantification-of-greenhouse-gas-ghg-emissions-and-removals-specification

[4] https://knowledge.bsigroup.com/products/bioenergy-with-carbon-capture-and-storage-beccs-quantification-of-greenhouse-gas-emissions-ghg-and-removals-specification

[5] https://ieaghg.org/publications/the-value-of-direct-air-carbon-capture-and-storage-daccs/

[6] https://ieaghg.org/events/webinar-value-direct-air-carbon-capture-and-storage-daccs/

Other articles you might be interested in

Get the latest CCS news and insights

Get essential news and updates from the CCS sector and the IEAGHG by email.

Can't find what you are looking for?

Whatever you would like to know, our dedicated team of experts is here to help you. Just drop us an email and we will get back to you as soon as we can.

Contact Us Now